Who is John Rawls and why should you care?

October 22, 2018

Originally published at the Acton Institute Powerblog

By Kevin Brown

Imagine asking a diverse group of rich, poor, attractive, unattractive, intelligent, unintelligent, white, non-white, educated, and non-educated — what makes a society just. Do you think you would get the same answer?

Neither do I.

Diverse individuals have diverse experiences, values, and contexts — and our varied backgrounds will inevitably color our perception of what is just, fair, and equitable. Given this, how can we as a society even begin to settle matters of justice when we have such different views of the world?

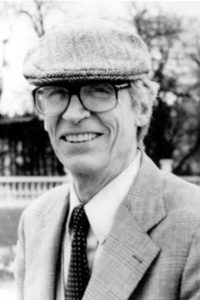

Enter John Rawls. Considered by many as the most important political philosopher in the 20th Century, Rawls — a Princeton educated Harvard Professor — was most famous for his 1971 work: “A Theory of Justice.” Rawls wanted to appraise society’s arrangements, institutions, and laws — not based upon what they can maximize — but on whether participants would agree to these structures in a neutral state.

But how can people encumbered with various particularities argue from a neutral state? Rawls answers with questions of his own. If you were allowed to construct the very society you were about to enter, but you did not know anything about yourself (geography, intelligence, ethnicity, family, attractiveness, health) — what Rawls calls a “veil of ignorance” — what would you choose? What principles of justice would you establish? What policies and precepts should govern the world you are about to enter?

This thought experiment — referred to as “the original position” — would, says Rawls, produce the following principles of justice. First, each person would be afforded equal basic liberties. Second, there would be equal opportunity for everyone, though not necessarily equal outcomes. Rawls’ final principle — and his most controversial — is what he calls the “difference principle.” This states that inequalities in society (such as wealth or income) are to be allowed only if they are to the greatest advantage of the least well-off in society. Put differently, inequality is permitted if this is the arrangement that makes the least well-off the best well-off.

There is much to value in Rawls’ philosophy — what he calls “Justice as Fairness.” For one, he promotes conditions of liberty as a necessary means to various ends. Further, Rawls recognizes that natural and social contingencies complicate fairness and equity. Fairness, for Rawls, demanded more than simply getting folks to the same starting line. Finally, in “Justice as Fairness” — the position of the least well-off is given primacy in society. In sum, Rawls revitalized a discussion around justice that persists to this day.

While Rawls’ philosophy offers much to appreciate, there are some lingering concerns — particularly as it is understood through the lens of the Christian faith tradition. First is the issue of fairness. Generally speaking, it is uncontroversial to aspire toward fairness or equity, but what is fairness? Should fairness be understood in terms of equal distribution? Merit? Need? Ability?

Moreover, as people of faith, we are recipients — not of God’s impartiality — but of his mercy (As Rev. Robert A. Sirico, Acton Institute president and co-founder once remarked, “Who of us will stand before the judgment of God and demand justice?”). Unlike Lady Justice, whose sword, scales, and blindfold represent justice as impartial and swiftly executed, God’s justice is moderated by his mercy toward us (as Thomas Aquinas writes, “justice has as its end charity”). This, of course, does not make fairness wrong — but in the faith tradition it is not our highest moral or relational aim.

Second, for Rawls, justice is realized in the procedure, not in the person. Indeed, he refers to affection for others as a “lower-order impulse” since it is an affront to one’s autonomy. Yet if I am created, and exist within a created order, then I am not fully autonomous. Rather, my capacity for flourishing will be intimately tied to my participation in the created order — which includes a love for God and for neighbor. Indeed, we are “relationally constituted” as John Wesley writes, making our relational sensibilities intrinsic to a good life.

Third, Rawls’ exercise is “tradition independent.” That is, to know what to do, we must abstract from our particularities. Our culture. Our context. Our background. Our attributes. Following philosopher Immanuel Kant, this line of reasoning says that we “construct” justice and the good. Why is this important? Because the exercise itself assumes there are no moral facts, no moral law, by which to correspond to — a clear departure from the Christian understanding of morality.

Finally, Rawls’ exercise is “liberal” in the sense that it does not presuppose any objective conception of what is good, right, and true. Rather, in justice as fairness, all conceptions of the good are equally valid. Of course, in the faith tradition, we don’t construct morality — we apprehend, pursue, and embody it. As St. Augustine famously wrote, virtue is ordo amoris, or “ordered love.” Loving the truly lovely; desiring the truly desirable. This is not something we create; it is something we participate in and, in doing so, experience fullness and satisfaction.

To be clear, these criticisms should not constitute an absolute dismissal of the thoughts, ideas, and artifacts emanating from Rawls’ philosophy or the liberal tradition.

While many are familiar with Rawls and his work, many are not. Regardless, there exists what I call a “Rawlsian reflex” when it comes to matters of understanding justice. Here, to ascertain the just arrangement or the “right thing to do” — it is common to appeal to fairness or impartiality, and further, to believe that we must set aside questions concerning morality, spirituality, and tradition.

The Christian faith calls us to a different response.

Justice is not best determined by abstracting from who we are. As philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre writes, “We are born into stories.” Our stories, moreover, are filled with morally relevant information that must be considered, not abandoned, when we deliberate about a good life or a good society. Nor can justice simply be about achieving fairness or impartiality. Fairness is often elusive, and is not as helpful as we might think in settling complex moral questions.

Finally, the Christian faith tradition recognizes that we do not simply construct the moral reality around us; we inhabit one. Thus, human flourishing will be necessarily bound up in recognizing that reality and participating within it.

Kevin Brown is associate professor of Business at Asbury University.

Rawls photo: Harvard University